What if…development before tectonics?

Written February 2026

For many of us, a topic on development and a topic on tectonics are mainstays of our KS3 geography curriculum. However, how should we sequence them? What if we teach development before tectonics? What if we teach tectonics before development? Does it matter? In this blog (as the title suggests), I’m going to argue that we should teach development before tectonics.

Largely thanks to the books and writing of Mark Enser (although, of course, others have written about this too) the challenges and opportunities of geography as a horizontal discipline have entered the lexicon of many of us. In the past, this was understood by some to mean that sequencing wasn’t (as) important in geography because, well, we could teach our curriculum in any order. Thankfully, we’ve largely progressed on from such thinking and, whilst there is no right or wrong answer with regards to the ‘best’ order in which to teach a Key Stage 3 geography curriculum, we are now all aware of the need to be able to articulate the ‘why this, why now’ thinking of our curricula. Why is this topic studied at this point? How does it build on the knowledge that has come before? How does it pave the way for what is to come?

And yet, I would argue that despite improvements in recent years, there is still more work to do with regards to achieving genuine progression across Key Stage 3 geography. It is easy to assume that as students learn about more places and understand more concepts, they’re becoming better geographers. Of course, in one sense, they are. And yet, what about what they’re able to do with this knowledge? What about their ability to draw links between different topics, different concepts and different regions of the world? Are they really getting better at ‘thinking like a geographer’?

I’d argue that if we don’t study development before tectonics then we’re missing one chance to unlock a key piece of the progression puzzle. Why? Well, here goes justifying this opinion…

Tectonic hazards feature in the KS3 National curriculum, most GCSE specs, and as a compulsory unit at A-Level. It is a topic familiar to us all and a favourite of many. But its appearance across KS3 to A-Level means that most A-Level geography students will have learnt about tectonic plates, earthquakes, and volcanoes three times in their 7-year journey. Now, whether or not this knowledge warrants study three times is a different conversation but, if we are allocating so much curriculum time to the teaching of tectonic hazards, then surely it is essential that we’ve given careful thought to what we’re teaching and why.

Allow me then to be a critical friend and ask why it is the case that, in so many schools, the KS3 study of tectonics is simply a watered-down version of the KS4 topic which is, in itself, a watered-down version of the KS5 topic? In the past, our tectonics lessons at KS3, KS4 and even KS5 may not have looked that different and so students ended up repeating much of the same information and knowledge rather than making genuine progress in their geographical understanding.

In the first two curriculums I taught, it’s fair to say that our tectonics topic probably lacked the very progression and rigour that I’m arguing for here. So, third time round, what have I done and why? This blog is part of a series sharing my thinking as I write the third KS3 geography curriculum of my career so far.

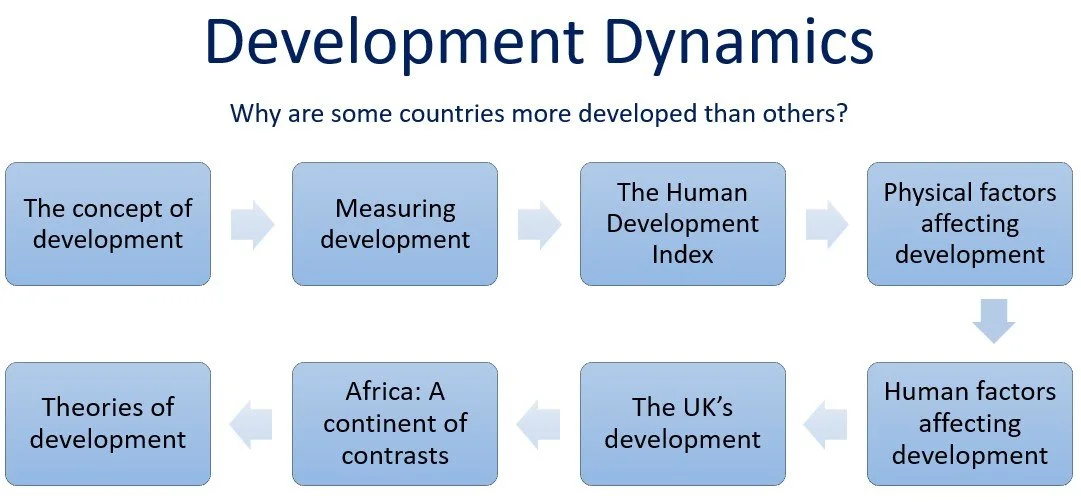

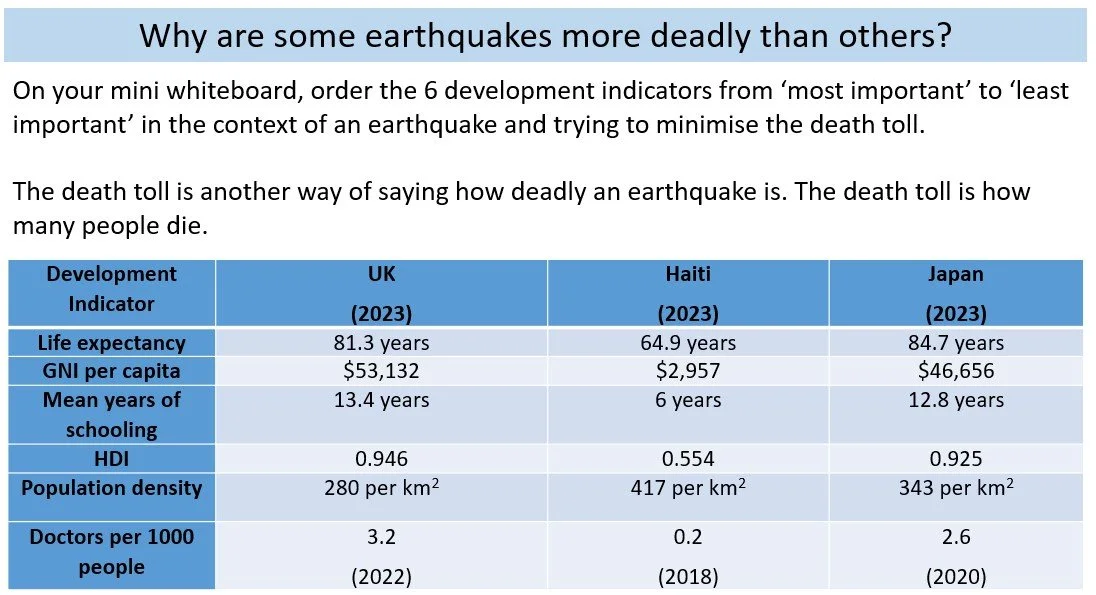

Our Year 8 curriculum begins with a rich exploration of globalisation as both a concept and a process before we conduct an on-site fieldwork investigation linked to this topic. From here, we move into our Key Stage 3 tectonics topic. And, as suggested above, our KS3 tectonics topic takes a different approach to that used in the past and which is perhaps most common in schools today. Whilst some of the key physical processes are learnt, our teaching of tectonics in Year 8 now gives equal weighting to the concepts of risk, resilience and vulnerability (all linked to development) by considering the complexity of factors that determine how deadly an earthquake is. This is only possible because they’ve studied development in depth in Year 7.

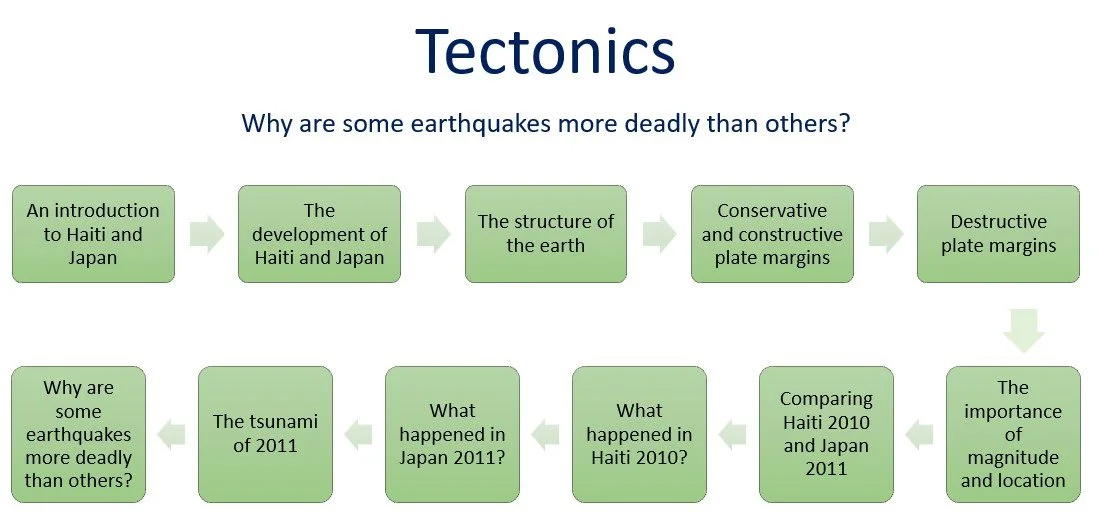

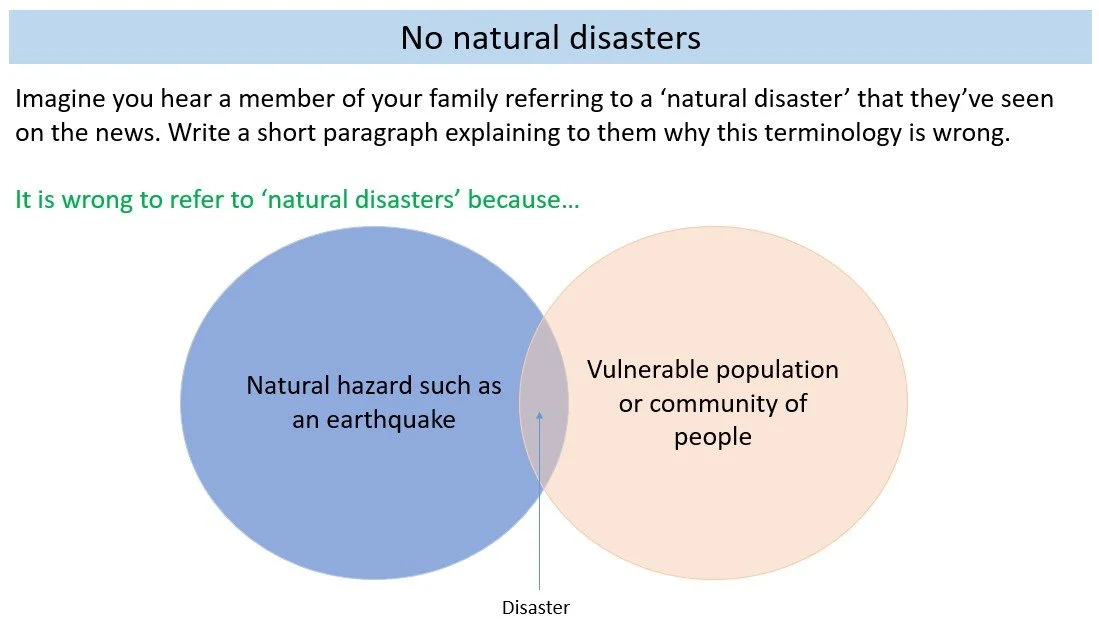

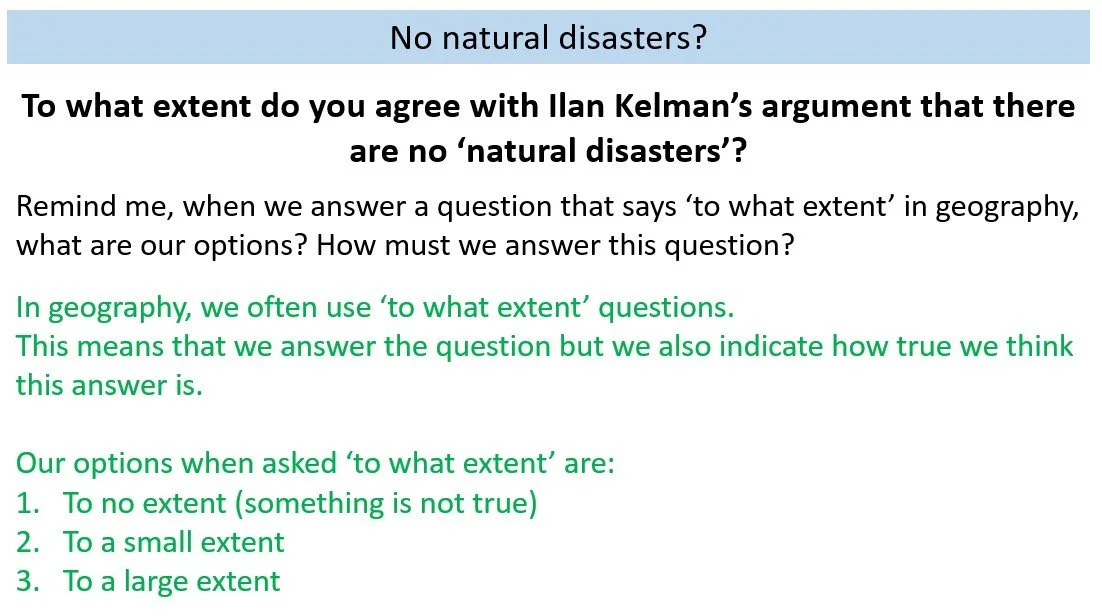

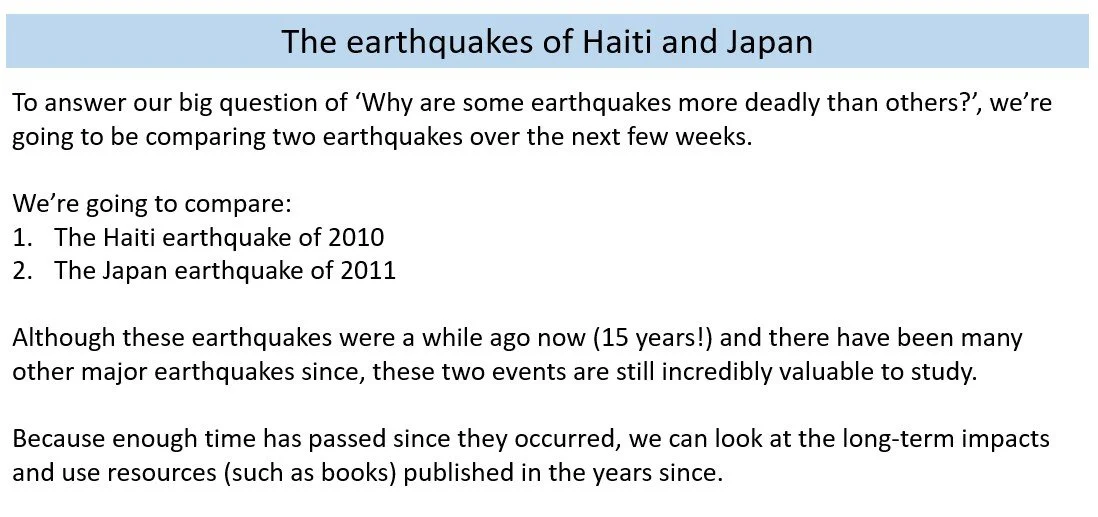

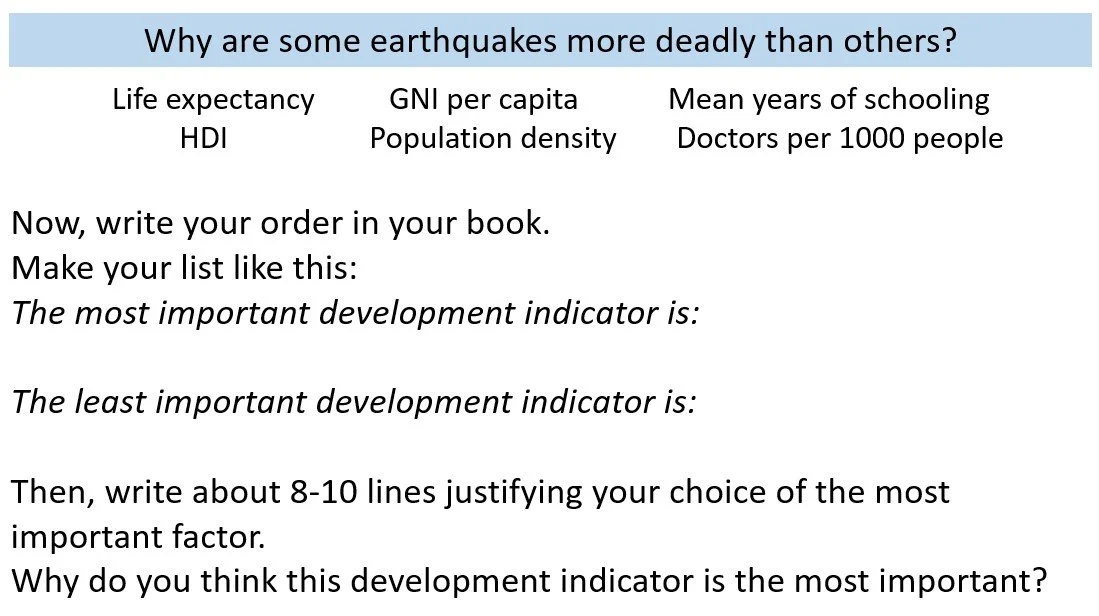

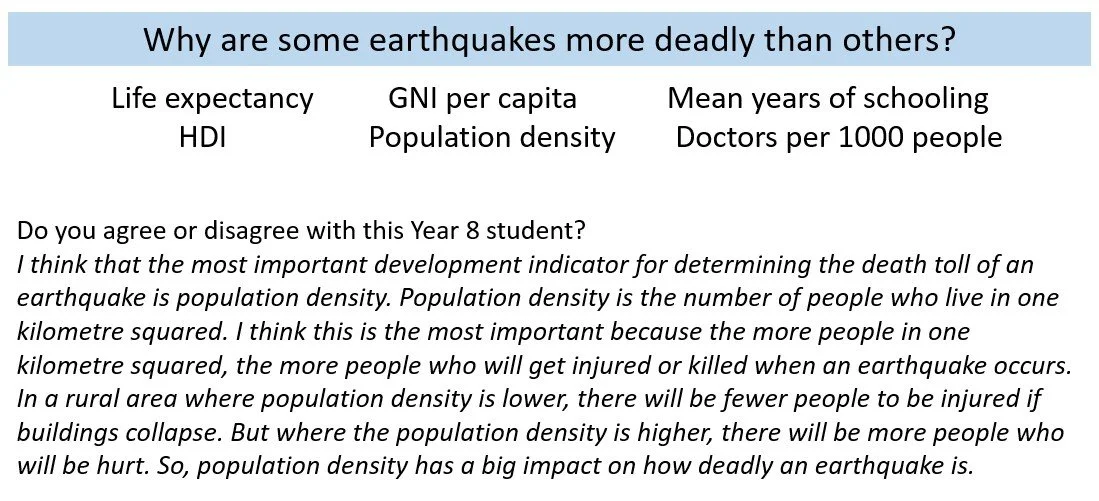

So, our big question for this topic is a ‘why’ question (Why are some earthquakes more deadly than others?). Whilst most of the Year 7 questions were ‘how and why’, Year 8 sees more challenging ‘who’ and ‘why’ questions as we begin to ask students to grapple with their knowledge and consider the significance and importance of different groups, factors and actions. Of course, in terms of the question itself, the wording of the question could be understood to imply that all earthquakes have a death toll or are deadly. This is obviously not the case and we implicitly address this through our discussion of arguments over the term ‘natural disasters’- a key part of this topic as we draw on the work of Ilan Kelman.

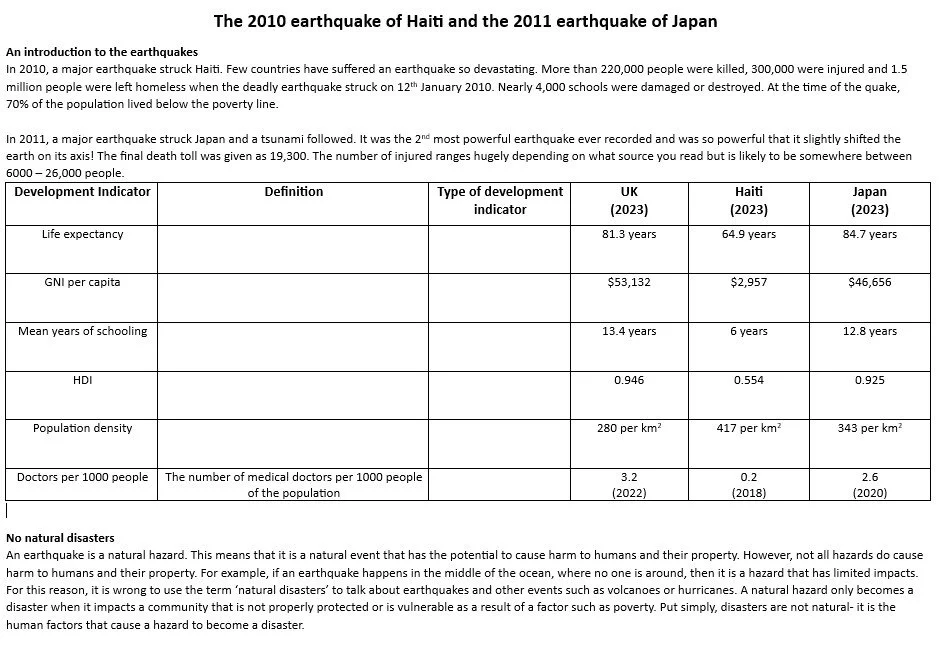

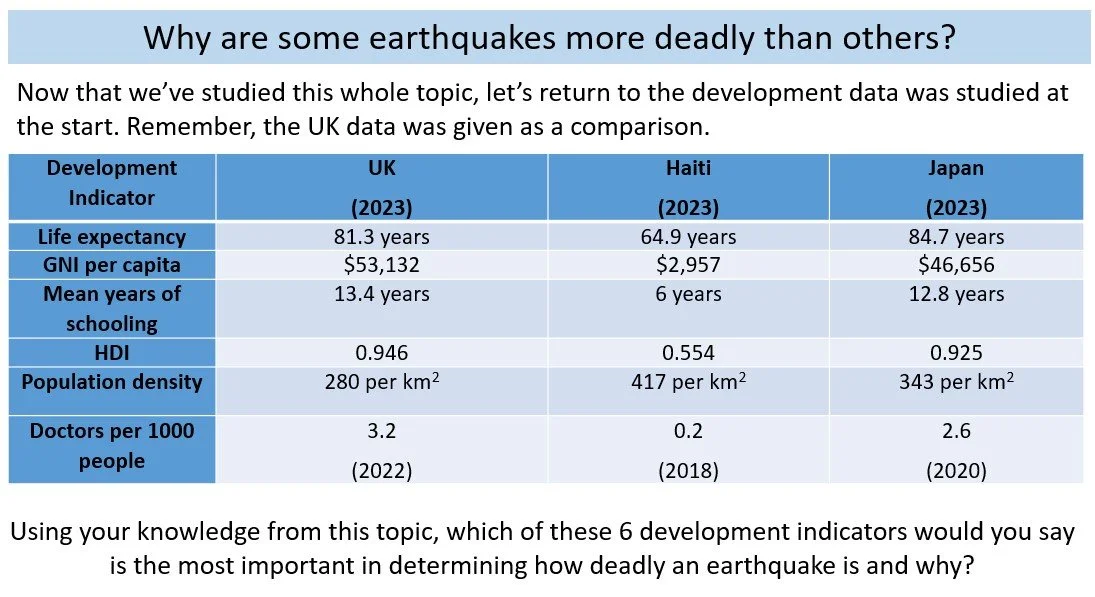

In order to answer this big question, the topic is centred around an in-depth comparison of the earthquake in Haiti (2010) and Japan (2011). Rather than have one or two lessons at the end of the unit to apply their knowledge to an example or case study, we’re centering the whole topic around our place-based examples to achieve our aim of greater conceptual understanding. So, in contrast to how many of us have likely taught tectonics in the past, the topic begins by stepping back: before students have learnt anything new about tectonics, we locate Haiti and Japan and compare the development level of each. Of course, this requires students to revisit and retrieve their knowledge from Year 7 development.

These lessons serve as an opportunity to recap, revisit and consolidate what students learnt in Year 7 Topic 3 Development Dynamics. A quick note then on the age of these case studies. Geographers are constantly debating when to switch case studies and how old is ‘too old’ for an example or case study. In my opinion, this debate is often over-simplistic and can focus on the wrong thing; it shouldn’t be about the age of the case study alone but about the rationale and justification for using it. To me, it doesn’t matter if the Haiti 2010 earthquake was now over 15 years ago if the rationale for teaching about it is sound. Yes, there have been several other earthquakes since that allow us to appear bang up to date but, as the screenshot from our lesson below shows, sometimes the ‘long view’ is useful in geography- it allows us to look back and assess the long-term impacts, lessons learnt and, of course, use high-quality resources and writing that has been published since.

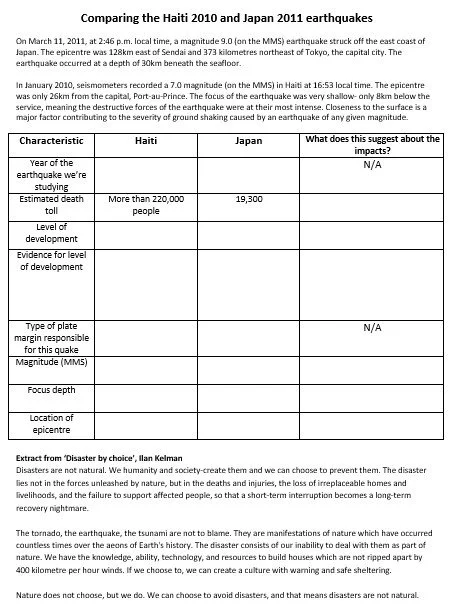

After these introductory lessons, students begin to learn about tectonic processes and hazards. They recall foundational knowledge gained in Year 7 when learning about Pangea and continental drift theory before gaining new knowledge about the structure of the earth and the difference between oceanic and continental crust. Despite adopting a different overarching lens for this topic, the core knowledge of the next few lessons will be familiar to all as we then apply this knowledge of the earth’s structure and plate movements to learn about conservative, constructive and destructive plate margins. Linking back to our in-depth examples, students learn that the 2010 earthquake in Haiti occurred on a conservative plate margin whilst a destructive plate margin was responsible for the 2011 earthquake in Japan.

As always, tough curriculum choices had to be made about what to leave out of this topic. Adopting a more synoptic conceptual lens through which to teach tectonics makes these decisions arguably even harder as, in order to make space for exploring how human development determines risk, resilience and vulnerability to natural hazards in both Haiti and Japan, some of the study of the physical mechanisms and processes of tectonics had to be removed. You’ll notice, for example, that in the sequence above, we don’t study the mechanics of how tectonic processes occur (e.g. convection currents and slab-pull and ridge-push).

As explained, this is a conscious effort to ensure that our KS3 tectonics topic does not repeat 90% of the same content that they’ll then repeat in Y10. We will teach more about tectonics and the physical mechanisms of tectonic processes but, once again, we’ll adopt a different lens to the topics of old. The drivers of plate movement, collision boundaries, volcanoes and ocean ridges will be taught later in KS3 during a different place-based study and serve as an opportunity to revisit, retrieve and consolidate the foundational knowledge gained in this initial tectonics topic.

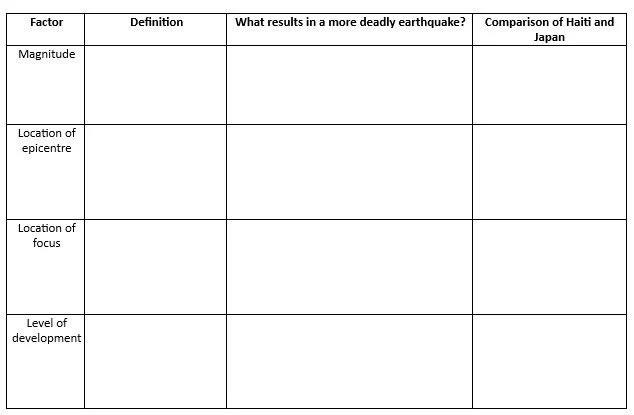

To begin exploring knowledge that directly relates to the big question, the significance of earthquake magnitude, the location of the epicentre, and the location of the focus is studied. This knowledge is constantly applied back to the Haiti 2010 and Japan 2011 earthquakes as the characteristics of these hazards are compared.

Having learnt about the different factors that affect the severity of an earthquake and looked at the characteristics of the earthquakes of Haiti and Japan, the next few lessons look explicitly at what happened when the earthquakes struck. Starting with the Haiti 2010 earthquake, students learn the difference between primary and secondary impacts and specific examples of each. Having previously been introduced to the work of Ilan Kelman, an extended extract from Disaster By Choice is used to explore the impacts in Haiti whilst a shorter extract from Ghosts of the Tsunami is used to look at what happened when the earthquake struck Japan in 2011. Students are asked to consider the differences between the impacts of the initial shaking in Japan and Haiti.

Students learn that whilst the shaking of the ground from the earthquake in Japan caused limited impacts, the tsunami that followed was devastating and resulted in 90% of the estimated 19,300 deaths. We explore what causes a tsunami and link this to what they know about the destructive plate margin that Japan sits atop. A second extract from Ghosts of the Tsunami is used to explore what it was like when the tsunami struck.

Finally then, it’s time to draw everything together and in the final lesson before answering the big question, we look explicitly at why some earthquakes are more deadly than others and consider the importance of the different factors learnt about in the context of Haiti and Japan. Again, the progression of knowledge from Year 7 Topic 3 to Year 8 Topic 2 is obvious; students are applying their knowledge of development directly to another context.

So, that’s how, third time round, I’ve written our KS3 tectonics unit. Nothing in this blog is revolutionary and I’m certainly not trying to claim it is. Rather, I’m hoping to provide some food for thought about the power of teaching development before tectonics and how, for me, it has been another piece of the puzzle for ensuring genuine progression of geographical knowledge and understanding throughout Key Stage 3 and beyond.

As always, all comments, challenges and questions welcome below!